- Home

- Catherine Lafferty

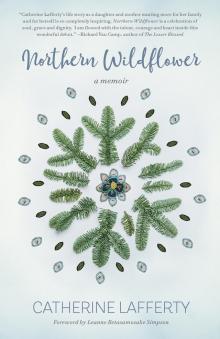

Northern Wildflower

Northern Wildflower Read online

Northern

Wildflower

Northern

Wildflower

a memoir

CATHERINE LAFFERTY

Roseway Publishing

an imprint of Fernwood Publishing

halifax & winnipeg

Copyright © 2018 Catherine Lafferty

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Editing: Leanne Betasamosake Simpson and Fazeela Jiwa

Cover beadwork: Norine Lafferty

Design: Tania Craan

eBook: tikaebooks.com

Printed and bound in Canada

Published by Roseway Publishing

an imprint of Fernwood Publishing

32 Oceanvista Lane, Black Point, Nova Scotia, B0J 1B0

and 748 Broadway Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3G 0X3

www.fernwoodpublishing.ca/roseway

Fernwood Publishing Company Limited gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Canada Council for the Arts, Arts Nova Scotia, the Province of Nova Scotia and the Province of Manitoba for our publishing program.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Lafferty, Catherine, 1982-, author

Northern wildflower / Catherine Lafferty.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77363-040-3 (softcover).--ISBN 978-1-77363-041-0 (EPUB).--

ISBN 978-1-77363-042-7 (Kindle)

1. Lafferty, Catherine, 1982-. 2. Chipewyan Indians--Canada--Biography. 3. Indian women--Canada--Biography. I. Title.

E99.C59L34 2018 971.004'972 C2018-903704-0

C2018-904496-9

To My Grandma

Acknowledgements

THIS BOOK WOULDN’T BE POSSIBLE without the help of many amazing, supportive and loving people that I have crossed paths with along my journey.

First, I would like to thank my children for being my most fierce critics and making sure that I don’t take things too seriously.

I’d like to thank my friends and extended family for supporting me in my writing journey and providing me with honest advice because that is what family and friends do best.

I’d like to thank my mentors Richard Van Camp and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson for being motivating, generous guiding lights. I am grateful for their valuable insight and the time they set aside for me.

To everyone in my life that has taught me to be strong, without life’s tough lessons I wouldn’t be the person I am today. Thank you for adding another layer of depth to my life and bringing out the bravery in me.

I’d like to thank my mom for always being patient with me, showing kindness and unconditional love.

I’d like to thank my grandparents for giving me everything I ever needed. They gave me just the right amounts of love, discipline, freedom and lifelong values and beliefs that I will forever stand for. I look forward to seeing you again.

MAHSI CHO!

This book was written in hopes of inspiring, encouraging and giving hope to the Indigenous Peoples of Canada that are in the struggle. Together we can break the cycle of intergenerational trauma and echo our voices loud and clear, in unity and solidarity, so that every person will understand the detrimental effects that colonialism has had on our livelihood throughout Canada’s history.

Foreword

BY LEANNE BETASAMOSAKE SIMPSON

I FIRST MET CATHERINE AT Dechinta Centre for Research and Learning — a Dene Bush University in Denedeh. Catherine was at one of our on-the-land gatherings as a councillor from the Yellowknives Dene First Nation. At the time, our programming was operating in the Akaitcho region of Denendeh on Chief DryGeese Territory — Catherine’s homeland. Catherine was there as a community leader, with her two gorgeous children, who immediately connected with my own kids. The group of them had a wonderful time over the next few days fishing nets, swimming, making dry fish and just being Indigenous kids. Together. At the time, I didn’t know Catherine was also a writer.

A few years later, Catherine emailed me to ask for help with a book-length memoir project she was working on. It has been rare in my life that young writers approach me with fully completed manuscripts, particularly Indigenous writers that have completed such enormous projects in relative isolation, with little support and encouragement from a writing community or any community for that matter. This has, however, been the beautiful struggle of generations of Indigenous writers, particularly Indigenous women. Catherine’s work immediately reminded me of Maria Campbell’s Halfbreed, Lee Maracle’s I am Woman and the poetry of Joanne Arnott. Even more importantly, it reminded me of Dene storytellers and the act of telling one’s own story as a practice of affirming our experiences, connecting to the ones that have come before us and our homelands and speaking our own truths on our own terms. Northern Wildflower also serves as a counterpoint to the academic work of Dene scholar Glen Coulthard because it represents a very personal, intimate exploration of the themes of dispossession, violence, disconnection and resistance from the perspective of a young Dene woman.

Often, in teaching in the North, I find it difficult to find relevant readings for my Dene students. I am excited to share Catherine’s book with them, because I know they will, perhaps for the first time, see their lives and their experiences in print. This was reinforced for me this year at Yellowknife’s writers’ festival, NorthWords. Catherine read an excerpt of her book to a packed room in the basement of the Yellowknife Centre on a panel with myself, Paul Andrew, Tracey Lindberg and Rosanna Deerchild — a pretty intimidating panel for an emerging Indigenous writer. Catherine read after Elder Paul Andrew spoke of his residential school experience and the strength and resilience of the Shuhtoatine or Mountain Dene. Her reading was powerful and moving, holding the audience in silence as she told her story. Her community connected with the work and that was wonderful to witness.

Memoir is not an easy genre, particularly for Indigenous women. We rarely get the opportunity to tell our stories, and when we do, we are often met with racism, patriarchy and judgement. I can’t think of any other young Dene women who have written memoirs, and that makes this story all the more important. From an artistic standpoint, it can be difficult to tell the story of our lives to audiences that may not fully understand the colonial context that is responsible for the violence in our lives. I think Catherine does an excellent job of truth telling while not succumbing to a victim narrative.

Northern Wildflower is a beautiful story of Dene resistance. It is a call for a just world, and it will inspire a new generation of young Dene writers and storytellers to speak up, to write and to live their very best lives.

— Leanne Betasamosake Simpson

Chapter 1

EVERYONE HAS A UNIQUE STORY TO TELL. This is mine. Memories strung together like beads, sewn onto smoked moose hide in the shape of a northern wildflower drawn by my grandmother.

My journey began on Easter Sunday in the early eighties. My parents were at a drive-through theatre in a small northern Alberta oil town when I made my debut into this world.

I proved to be fiery from the start. I had light red hair and eyebrows that would turn bright red when I cried; I was born with a passion that I couldn’t hide. I get my auburn traits from my dad, a freckle-faced redhead from the east coast. I get my brazen personality from my mother, a black-haired beauty one generation away from being born in a teepee.

I cried nights on end whi

le they walked the floors with me in their small apartment. My mom often reminds me that no one ever wanted to babysit me because I cried too much. I was colicky and inconsolable.

My mom would rock me in my homemade Dene swing made from a sheet, some rope and two sticks, which hung from one corner of the ceiling above her bed to the other. A Dene invention was the only thing that would help me fall asleep — no wonder I like hammocks so much.

It’s safe to say that I was a restless child from my entrance into this world, and I’ve carried this feeling of yearning in my heart throughout my life.

I have a constant irritation with the status quo and am rarely satisfied. I always want more. Not in the sense of material things but in the sense of wanting a better world, a just world, especially for those who grew up like me, knowing what it’s like to live as an outsider on your own territory. Knowing what it feels like to grow up in a system that doesn’t accept you, the same system that forced you to be dependent on it.

I want there to be a better world for Indigenous people who have felt what it’s like to live in a society that has already developed a preconceived notion that we are failures, that we have a meek future, that we will end up drunk like the parents that couldn’t raise us, that we will end up abusing the system with our countless needs of taxpayer dollars, that we are not worthy to eat at the big table, that we should be thankful and consider ourselves lucky enough to live off the crumbs they give us. There has got to be something better for those who know what it’s like to feel hopeless and disingenuously pitied by those who watch us fall through the cracks because they believe there’s no hope for us. We aren’t even considered human, after all. The worst part is that some Indigenous people also have this perception of themselves and where they come from because they have lost their cultural identities through social conditioning efforts.

I want justice. I want to take back our stolen identities. Our pride has been ripped and torn to shreds from the years of deliberate trauma that was served to us in the form of righteous, all-knowing authority. The wicked rules that have been written in a heavy ink are made to look like they can’t be erased, but those rules can be broken, those policies can be amended, those laws can be overturned and those words that hold us down can be burned.

I want our men to be warriors again and our women to be safe and respected. I want our land back, our homes back, our families back, our health back. We were forced to detach from everything we knew right down to the very core of who we are. I want things back to the way they once were. The Dene once lived in harmony without interruption and influence, and that worked well for us. I won’t be fully satisfied until I see the day that we are no longer told to do things any other way but the way we know, our way.

I won’t be content until the day that I feel like I belong on my own soil. Until the day that I don’t have to work twice as hard to get that management job even though I have a higher education. Until the day that I don’t walk past the post office and see my relatives on the street being ridiculed and stereotyped for being intoxicated and homeless. Until the day I never hear another Indian joke. Until the day that I don’t have to worry that my son will end up in jail because he was profiled and discriminated against. Until the day that I don’t have to worry that my daughter will be abused because she’s considered worthless in the eyes of those who feel they are superior to her. Until the day I don’t have to argue with someone when I hear them say, “Why can’t you just get over it?” Until the day that everyone understands why we won’t get over it.

Until then, I will not rest. I will keep fighting the good fight to make sure I see a change in this world, until the silenced voices can speak again. Until we can make our own rules and until we can be sure that no one takes advantage of us anymore. I didn’t know these injustices existed when I was brought into this world, but I could feel them through my mother’s womb and as time went on I inevitably encountered them in my everyday life.

My family grew up constantly struggling on our own land when we should have been treated like royalty, with the respect and dignity we deserved. Instead, we were forced to assimilate, often violently. Our minds, bodies and self-determination were not and are still not respected to this day. Our vision of our treaty is continually erased, and we are always having to stand up for our rights even in the most mundane circumstances. It’s tiring.

I don’t think our people ever realized the full extent of how the future for them would unravel. No one except the Elders could have predicted the impacts that would send a generational ripple of devastation throughout Canada. The Elders always talk about how money encroached upon their livelihood. The few Elders that are still alive today witnessed first-hand how our people slowly started to become more and more reliant on it. Money eventually became too powerful of a force to stop. “Money doesn’t grow on trees,” my mom would say, and I would say, “Yes it does, it’s made of paper.” It took me a long time to realize that money was earned through working for other people and not for ourselves.

In the olden days, when our people worked they worked with their hands on the land because it was the only way to survive. They worked hard for their food and shelter and they enjoyed it. There was no such thing as being idle. Then, something happened when money crept into the North. Our people did not fit into the new working world because they had little to no formal education, and they weren’t readily accepted into the mould that was determined fitting enough to obtain the jobs that were created when the government and the mining industries welcomed themselves in. The North became a rewarding scene for southerners seeking adventure, new beginnings and prosperity. This left little room for the Dene, who did not require those things to be happy, and almost overnight the Dene way of living almost disappeared through the exclusiveness of those who celebrate money.

As a child, I couldn’t grasp the concept or the importance of money and how it was something that people strived to obtain all their lives. As an adult, I still don’t understand why most of us spend our lives racing to get to the top, breaking our backs in the process and struggling to make ends meet only to end up counting down until retirement.

There has got to be more to life. I want a deeper fulfillment. I want my soul to be full of purpose and substance. I don’t want to drag myself out of bed every morning cringing at the thought of the work week ahead of me. I want to jump up out of bed every morning knowing that I am doing what I love without restriction, without worrying about money.

Unfortunately, until that day comes, money makes the world go around and enriches our lives with a false sense of happiness, materialism and security. Maybe I have come to think that it shouldn’t have to be this way because of my humble beginnings.

My first memories are of my parents throwing small parties in our tiny concrete basement suite just outside of Toronto, a skip and a hop away from the busiest highway in North America. I could see them from the crack in my bedroom door, laughing and dancing in the middle of the night and listening to country music long after I had been sent to bed. But I was a night owl and tried to stay up just as late as they did. I could barely see them with my vision a blur, so I would squint hard just to see the outline of their figures — I had bad eyes, but my mom didn’t know I needed glasses yet.

During the day, my dad would go to work building houses while my mom and I curled up on the couch together and watched game shows as I ruffled her hair. I’ve always been fascinated with hair and used to pretend I was a hairdresser. My best friend Sarah lived across the street from me and she would come over to play. Sarah and I decided to play hairdresser one day before class pictures. I was the hairdresser and she was the client. My grandma happened to be visiting us and I snitched her sewing scissors from the kitchen table. Sarah and I hid in the bathroom until my mom noticed that we were too quiet. “Catherine, you open this door right now!” She banged her fist on the locked bathroom door, insisting that I open it. I reassured her that I

would just be a few more minutes, but I knew I was in trouble. When Sarah came out of the bathroom, her once-beautiful, long, strawberry-blonde hair was snipped short and stuck flat to her head with a few spikes sticking up here and there. I still have her school picture tucked away somewhere, reminding me that hairdressing is not my calling.

Catherine with a juice stained mouth and pearl hoop earrings (photo credit Norine Lafferty)

In those days, I used to play with two brothers, Robby and Billy. Our moms were best friends, so they would often come over to visit us. One day Robby accidently ripped one of the little golden hoop pearl earrings right out of my ear while he was wrestling with me, and I screamed in pain. I had worn those earrings ever since I was a baby. My mom had brought me to get my pointy elf ears pierced for my baby pictures when I was just learning how to sit up by myself. She had seen a little girl from India who had her ears pierced and thought it looked cultural.

I wonder how my mother felt moving to such a big city after living in a small northern town her entire life. I know she lived in fear of losing me when we were out in public, so she would part my hair down the middle and braid both sides, then tie a little bell at the bottom of each braid so she could hear me running around the grocery store if I wandered too far. So, it’s safe to say she almost suffered a heart attack when I didn’t listen after she told me to hold onto her pant leg while she was in line at a food truck vendor at an outdoor country music concert with over one hundred thousand people. My parents searched for almost an hour and had people join the search, yelling out my name on the lookout for a little Dene girl with ornamental braids, until my dad found me crying at the front of the stage near the fenced-off area. I remember looking up to see his shadow hovering over me, half angry and half relieved.

Northern Wildflower

Northern Wildflower